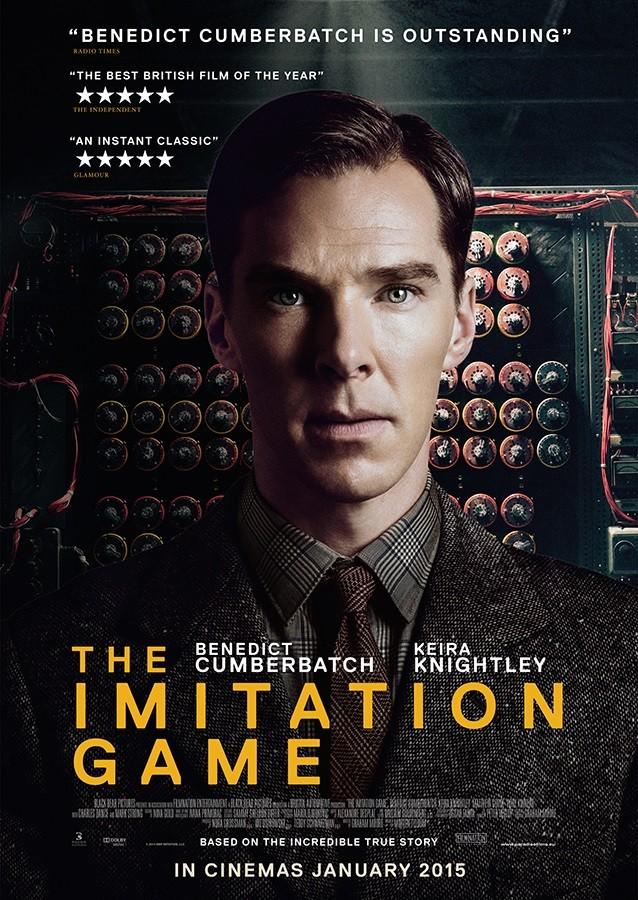

Movie Review: The Imitation Game

January 25, 2015

While it is unsurprising to see Benedict Cumberbatch play yet another eccentric genius, it is delightful nonetheless. “The Imitation Game” features Cumberbatch as Alan Turing, a brilliant yet awkward mathematician who builds a machine that can crack Nazi Germany’s encryption code, the Enigma Code, thus significantly shortening the war and saving millions of lives.

It may be another World War II film, but “The Imitation Game” stands out as it places focus away from the battlefield and on England’s Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park where Turing, along with a team of other code-breakers, work in secret. The war, however, is not ignored as glimpses of the carnage are spread intermittently throughout as a reminder of the high stakes. The high death rate of the war, along with a race against time as government support for Turing’s code breaking machine (named “Christopher” in the film) dwindles, culminates in a fulfilling “aha” moment when Turing discovers the key to cracking the code.

The film’s strongest feature is Cumberbatch’s acting. He skillfully portrays Turing as arrogant but socially awkward. It would be difficult not to compare his portrayal of Turing to his most well known role on BBC’s Sherlock, a modern-day adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s mystery series, as the titular character. However, unlike Sherlock, Cumberbatch’s Turing is less confident in himself; he is vulnerable. His pauses and facial expression play into the character’s timid nature. This proves essential to the story as it reflects Turing’s tragedy.

The story is split between three times: Turing’s childhood in the late 1920s, his work on the cracking the Enigma Code during World War II, and his fate after the war in the 1950s. The majority of the film takes place during World War II, switching to the other two timelines to provide to the underlying plot of Turing’s prosecution as an admitted homosexual, a crime in England at the time. The 1920s story focuses on Turing coming to an understanding of his sexuality due to his feelings for his closest friend, Christopher, for whom he names his code breaking machine. It also supports the film’s central idea that Turing’s oddness is what enabled him to do the impossible feat of cracking the Enigma Code. The 1950s story serves as the present for the film in which Turing tells his story, kept confidential by the British Government, to a police officer during an interrogation into his gross indecency, the crime which homosexuals were pegged with. The tragedy is that he is branded as a criminal for his sexuality instead of as a hero for shortening the war.

“The Imitation Game” also boasts one of the best film soundtracks of the past few years. It is engaging and mysterious when focusing on the code cracking and solemn when focusing on Turing’s misfortunes throughout.

The film does have some weak spots despite how strong it is as a whole. There is a subplot involving a soviet spy within Turing’s group, but this seems more of a distraction rather than a genuine issue. I would pardon it if it had a historical basis, but there is none; it was simply added to the script as a source of additional drama. This is not the sole historical inaccuracy of the biopic. For example, Turing’s machine is falsely named “Christopher” after when its actual name was Bombe. The design was not Turing original idea either. Rather, he increased the speed that the Bombe invented by Polish inventors in 1939 processed by programming it to search for certain letters. There are several other inaccuracies, especially in the portrayal of certain key characters. This does not detract from the viewing experience in any way. The characters are well developed and relatable (even Turing to an extent). However, one would expect a film with the intent to present the story of a hero wrongfully persecuted and give a posthumous pardon a year ago to adhere strongly to the biography the script was based on.

There were a few clichés with certain characters as well. Charles Dance as Commander Denniston, the rigid military officer that does not believe in the Turing’s machine, and Matthew Goode as Hugh Alexander, the chess champion that clashes with Turing for leadership over the group of code-breakers, are the most one-dimensional characters. It seems that their main role throughout the film is to hinder the protagonist’s efforts. There is also the cliché change of heart when Turing’s peers band together to prevent his firing when they had previously loathed him. These moments would be forgivable if they were based on actual occurrences, but they are not. Denniston was supportive of Turing from the start and Alexander cooperated well with Turing.

Despite the few problems with historical inaccuracies and some clichéd moments, “The Imitation Game” is one of the best films to come out in 2014. It is difficult to find fault with the film; most of my gripes came after I watched the film and looked into Turing’s story. Most people watching this film will not know anything about the father of theoretical computer science whose work would inspire the creation of modern computers. The film is successful in introducing his incredible feats during the war as well as his tragic fate. Benedict Cumberbatch has made Alan Turing a fascinatingly odd, yet charming, character. You can’t help but want Turing to succeed even though he doesn’t have the warmest personality. You can admire him because, as the film puts it, “sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.”